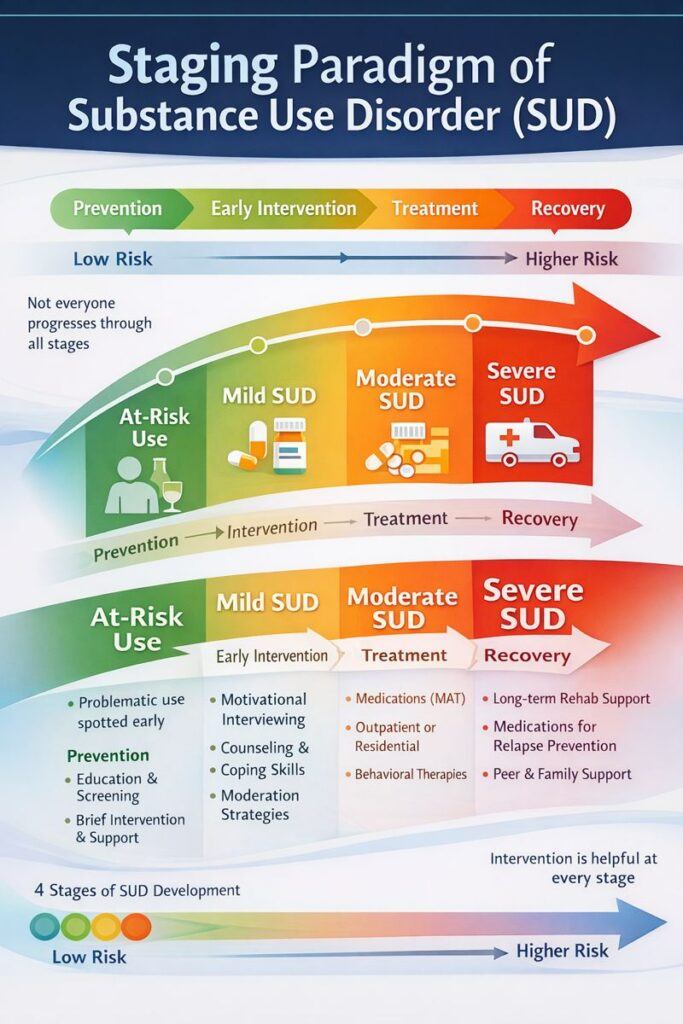

The SUD staging paradigm provides a structured framework by dividing substance use into distinct phases, from initial experimentation to full recovery. This approach allows interventions, family support, and community resources to be tailored to the individual’s current stage, ensuring that prevention efforts target early use, treatment focuses on dependence or severe SUD, and relapse-prevention supports long-term recovery. By aligning care with the stage of substance use, this paradigm promotes more effective, coordinated, and patient-centered support, improving outcomes for both individuals and their families.

The Staging Paradigm of Substance Use Disorder: Understanding Addiction in Phases

The staging paradigm of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) is a conceptual framework that views addiction as a progressive condition developing through distinct phases or stages. This model helps clinicians, families, and individuals understand how substance use evolves, guiding treatment and intervention strategies tailored to each stage.

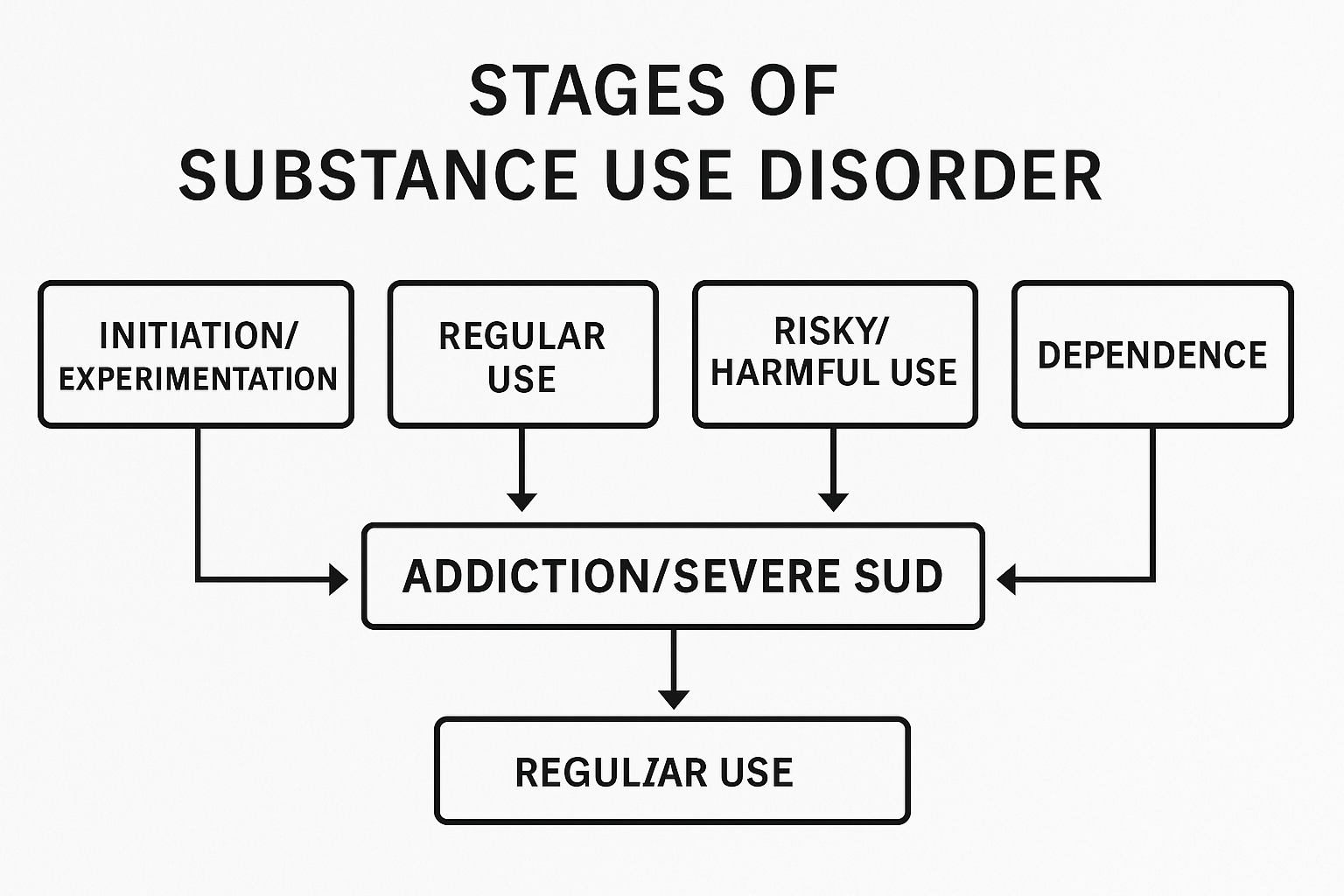

Key Stages in the Staging Paradigm of SUD

1. Initiation/Experimentation

- Initial use of a substance, often out of curiosity, social pressure, or as a way to cope with stress.

- Substance use is usually occasional and not yet problematic.

2. Regular Use

- Use becomes more frequent, though it may still feel controlled or tied to social settings.

- Patterns of use begin to form, though significant negative consequences may not yet be present.

3. Risky/Harmful Use

- Substance use begins to disrupt daily life (e.g., health concerns, strained relationships, workplace or legal problems).

- Tolerance, cravings, and continued use despite adverse effects start to develop.

4. Dependence

- Both physical and psychological dependence emerge.

- Withdrawal symptoms appear when the substance is not used.

- Increasing difficulty in controlling use.

5. Addiction/Severe SUD

- Compulsive, uncontrolled use despite severe negative consequences.

- Substance use dominates priorities, behaviors, and decision-making.

- High risk of relapse without appropriate treatment and long-term support.

Importance of the Staging Paradigm

- Early Intervention: Recognizing the early stages of substance use allows for preventive strategies before addiction fully develops.

- Tailored Treatment: Each stage requires a unique approach, from brief motivational interventions to comprehensive rehabilitation.

- Monitoring Progression: Provides a roadmap for tracking changes in substance use behavior and adjusting care plans accordingly.

👉 By understanding addiction as a progressive condition, the staging paradigm highlights that timely recognition and intervention can change the trajectory of someone’s recovery journey.

Stage-Specific Interventions in Substance Use Disorder: How the Staging Paradigm Transforms Care

Using the staging paradigm of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) changes intervention strategies by making them more stage-specific, targeted, and proactive rather than reactive. Instead of applying a one-size-fits-all approach, this model emphasizes a tailored strategy at each stage of substance use and recovery.

1. Early Stages (Initiation/Experimentation & Regular Use)

- Focus: Prevention and education.

- Intervention Shifts:

- Implement school- and community-based prevention programs.

- Address peer pressure and misinformation about substances.

- Promote healthy coping skills and alternative activities.

- Screen for early mental health concerns that may increase risk.

2. Risky/Harmful Use

- Focus: Early intervention before dependence develops.

- Intervention Shifts:

- Apply brief motivational interviewing in primary care, ERs, or workplaces.

- Connect individuals with outpatient counseling or peer support.

- Engage families in recognizing and responding to warning signs.

- Use harm reduction approaches such as safe use education and overdose prevention.

3. Dependence

- Focus: Treatment engagement and stabilization.

- Intervention Shifts:

- Initiate evidence-based therapies like CBT or contingency management.

- Begin medication-assisted treatment (MAT) when clinically indicated.

- Integrate family therapy to strengthen support systems and address codependency.

- Provide coordinated care for co-occurring mental health disorders.

4. Addiction / Severe SUD

- Focus: Intensive treatment and relapse prevention.

- Intervention Shifts:

- Enroll in residential or intensive outpatient programs.

- Continue MAT with close monitoring and adjustments.

- Implement structured relapse prevention planning.

- Engage community recovery supports, such as peer specialists and sober living environments.

5. Recovery & Recurrence Risk

- Focus: Long-term support and reintegration.

- Intervention Shifts:

- Provide ongoing peer recovery coaching.

- Support reintegration into work, education, and community life.

- Maintain regular relapse-prevention check-ins.

- Involve family members in sustaining a recovery-friendly environment.

👉 By aligning interventions with the stages of SUD progression and recovery, the staging paradigm makes prevention and treatment more effective, adaptive, and sustainable over the long term.

Stage-Specific Self-Management in Substance Use Disorder: Adapting Recovery Strategies

Using the staging paradigm changes self-management strategies by making them progressive and stage-specific. Instead of a “one-size-fits-all” recovery plan, individuals adapt their skills and actions based on where they are in the substance use continuum. This flexible approach empowers people to take practical steps that align with their stage of risk, dependence, or recovery.

How Self-Management Strategies Shift by Stage

| Stage | Self-Management Focus | Stage-Specific Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initiation / Experimentation | Avoid escalation | • Learn refusal skills for peer pressure • Set clear personal boundaries • Engage in safe, substance-free hobbies • Track emotions and triggers early |

| 2. Regular Use | Recognize patterns & risks | • Keep a personal substance use log • Identify emotional/situational triggers • Replace risky social circles with healthier ones • Seek early counseling if warning signs appear |

| 3. Risky / Harmful Use | Reduce harm & seek help | • Use harm reduction tools (e.g., naloxone, safe use spaces) • Limit frequency or quantity while working toward abstinence • Practice mindfulness or stress-management daily • Create a “concern list” of impacts on health, work, or relationships |

| 4. Dependence | Commit to treatment & stabilization | • Follow treatment plan & medication schedule • Attend all therapy and support group sessions • Build a relapse prevention checklist • Develop a daily structured routine |

| 5. Addiction / Severe SUD | Intensive recovery work | • Maintain full engagement in residential/IOP programs • Use daily recovery journaling • Have a “crisis plan” for high-risk urges • Strengthen sober peer network |

| 6. Recovery & Recurrence Risk | Long-term recovery maintenance | • Continue aftercare meetings and therapy • Monitor for early relapse warning signs • Keep a flexible coping plan for stressors • Set and pursue life goals beyond recovery (career, relationships, hobbies) |

👉 By aligning self-management with the staging paradigm, recovery becomes more realistic and sustainable. Each stage has its own set of challenges, but also unique opportunities for growth, prevention, and healing.

Stage-Matched Family Support: Guiding Loved Ones Through the Journey of Substance Use Disorder

Using the staging paradigm of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) allows families to move from a reactive, crisis-driven approach to a proactive, stage-specific support system. By understanding the unique needs of their loved one at each stage—from experimentation to recovery—families can provide guidance, set healthy boundaries, and foster resilience.

The table below outlines how family support evolves across the stages of substance use, with practical strategies tailored to each phase. Whether it’s encouraging open communication during experimentation or offering structured recovery support in severe SUD, these strategies help families become an active part of the healing process.

Here’s how strategies change at each stage:

| Stage | Family Support Focus | Stage-Specific Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initiation / Experimentation | Prevention & open communication | • Have honest, non-judgmental conversations about substance risks • Encourage healthy social and recreational activities • Model responsible coping skills and stress management • Set clear expectations and boundaries early |

| 2. Regular Use | Early recognition & guidance | • Monitor for changes in behavior, mood, or friends • Gently express concern and share observations • Offer to connect the person to counseling or prevention programs • Avoid enabling behaviors while staying emotionally supportive |

| 3. Risky / Harmful Use | Support harm reduction & help-seeking | • Help access harm reduction resources (naloxone, safe use education) • Attend educational sessions about substance use • Encourage evaluation by a healthcare professional • Set and uphold clear family boundaries |

| 4. Dependence | Engagement in treatment & stability | • Participate in family therapy sessions • Support attendance in treatment and recovery programs • Provide stable housing and reduce environmental triggers • Learn about addiction as a medical condition |

| 5. Addiction / Severe SUD | Intensive recovery support | • Engage in structured family recovery programs (e.g., Al-Anon) • Offer practical help—transportation, childcare during treatment • Avoid conflict escalation during high-stress moments • Maintain consistent boundaries to avoid enabling |

| 6. Recovery & Recurrence Risk | Long-term encouragement & relapse prevention | • Celebrate milestones and progress • Remain alert to early relapse warning signs • Encourage ongoing therapy or peer support • Support life goals beyond recovery, like education and career advancement |

Stage-Matched Community Resources: Supporting Individuals Through the Journey of Substance Use

Using the staging paradigm of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) allows communities to provide interventions that are tailored to each individual’s stage of substance use, rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach. By aligning community resources with the person’s specific needs—ranging from prevention and early intervention to intensive treatment and long-term recovery—local programs can maximize impact, reduce harm, and promote sustained recovery.

The table below outlines how community support strategies evolve across the stages of substance use, offering practical examples of programs and services that address the unique challenges at each stage of the addiction and recovery journey.

Here’s how it shifts at each stage:

| Stage | Community Resource Focus | Stage-Specific Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initiation / Experimentation | Prevention & education | • School-based prevention programs • Youth mentorship and sports/recreation programs • Social media campaigns on risks and healthy choices • Community skill-building workshops |

| 2. Regular Use | Early intervention | • Screening and brief intervention programs in schools, clinics, and workplaces • Peer support outreach (youth peer leaders, recovery coaches) • Drop-in centers for counseling • Educational workshops for at-risk groups |

| 3. Risky / Harmful Use | Harm reduction & engagement | • Needle/syringe exchange and naloxone distribution • Mobile health vans for screening and counseling • Crisis helplines and chat services • Outreach programs in nightlife and street settings |

| 4. Dependence | Treatment access & stabilization | • Affordable outpatient/inpatient treatment programs • Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) clinics • Case management and housing support • Transportation assistance for appointments |

| 5. Addiction / Severe SUD | Intensive treatment & crisis care | • Long-term residential recovery programs • Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) • Mental health crisis stabilization units • Employment and skills training programs for recovery |

| 6. Recovery & Recurrence Risk | Long-term recovery support | • Recovery community centers • Sober housing and alumni programs • Peer mentoring networks • Education, job placement, and life skills training |

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some common questions:

Question: What are the disadvantages of using the Staging SUD paradigm?

Answer: The staging paradigm of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) conceptualizes addiction as a progressive condition that unfolds through distinct stages (e.g., initiation, escalation, maintenance, and potential recovery). While this framework has advantages for structuring interventions and understanding progression, it also has several disadvantages and limitations:

1. Oversimplification of Addiction

- Addiction does not always follow a linear progression. Some individuals may skip stages, regress, or experience multiple stages simultaneously.

- Treating SUD as a rigid sequence can overlook the complexity and individual variability of substance use patterns.

2. Risk of Labeling and Stigmatization

- Assigning someone to a specific “stage” may inadvertently stigmatize them or make their condition feel fixed and unchangeable.

- Individuals may be pigeonholed, limiting personalized care or ignoring co-occurring disorders.

3. Limited Predictive Accuracy

- The model may not accurately predict who will progress to severe stages or who will respond to treatment.

- Environmental, genetic, and psychosocial factors can cause substantial deviations from the predicted stage path.

4. Neglects Contextual and Social Factors

- Focusing primarily on stages emphasizes internal progression rather than external influences such as family, community, socioeconomic status, and trauma.

- It may underplay the role of social determinants in initiating or sustaining substance use.

5. Potential for Treatment Inflexibility

- Clinicians might tailor interventions too rigidly to the stage rather than to the patient’s specific needs.

- For example, a person in an “early” stage might benefit from harm reduction strategies typically reserved for later stages.

6. Difficulty in Stage Assessment

- Stages are often defined conceptually rather than by clear biomarkers or objective criteria.

- Misclassification is common, making it challenging to apply the paradigm consistently in clinical settings.

7. May Underestimate Recovery Potential

- The model implies progression toward worsening addiction unless treated, which may underestimate spontaneous remission or natural recovery without formal intervention.

In short, while the staging paradigm is functional for conceptual clarity and educational purposes, it is not a one-size-fits-all model. It should be complemented with individualized assessment, consideration of environmental and psychological factors, and flexible treatment planning.

Question: What are the ethical dilemmas of using the Staging SUD paradigm?

Answer: Using the staging paradigm of SUD raises several ethical dilemmas because it frames addiction as a predictable, progressive condition. While helpful for clinicians and researchers, it can unintentionally lead to practices that conflict with ethical principles in medicine, psychology, and social work. Key dilemmas include:

1. Risk of Stigmatization and Labeling

- Assigning someone to a particular stage of addiction can label them as “problematic” or “severe,” potentially reinforcing social stigma.

- Ethical concern: This may harm self-esteem, social identity, and willingness to seek help.

2. Determinism vs. Autonomy

- The paradigm may imply that progression through stages is inevitable unless intervention occurs.

- Ethical concern: This can undermine patient autonomy by framing recovery as a fixed path rather than a choice, possibly influencing treatment decisions without full patient consent.

3. Potential for Inappropriate Resource Allocation

- Clinicians may prioritize treatment based on stage rather than individual need or urgency.

- Ethical concern: Patients in “early” stages may receive less support, while those in “advanced” stages might get more resources, which may not align with justice or equity principles.

4. Oversimplification Leading to Misdiagnosis

- Using stages rigidly may ignore comorbidities or unique patient circumstances.

- Ethical concern: Misclassification could lead to ineffective or harmful treatment, violating the principle of nonmaleficence (“not harm”).

5. Confidentiality and Disclosure Risks

- Documenting a patient’s “stage” could inadvertently influence insurance coverage, employment, or legal decisions.

- Ethical concern: This raises privacy concerns and potential discrimination.

6. Neglecting Social Determinants

- The model focuses on internal progression, potentially underemphasizing environmental, cultural, or socioeconomic factors.

- Ethical concern: Ethical practice requires acknowledging these influences to avoid blaming the individual for their addiction.

7. Potential Pressure to Conform to the Model

- Clinicians may feel pressured to treat according to stage rather than tailoring interventions to individual preferences.

- Ethical concern: This can conflict with respect for persons and patient-centered care.

In essence, the ethical dilemmas revolve around balancing clinical utility with respect for autonomy, justice, nonmaleficence, and privacy. Using the staging paradigm responsibly requires careful, individualized application and awareness of these risks.

Question: What are examples of Labeling and Stigmatization by using the staging SUD paradigm?

Answer: Using the staging paradigm of SUD can unintentionally lead to labeling and stigmatization, because it classifies individuals into discrete “stages” that suggest fixed characteristics or a predictable trajectory. Here are concrete examples:

1. Labeling Someone as “Severe” or “Chronic.”

- A patient categorized in a later stage (e.g., “maintenance” or “advanced”) might be labeled as a chronic addict, implying that recovery is unlikely.

- Effect: Healthcare providers, family, or employers may see them as “beyond help,” reducing support and opportunities for recovery.

2. Assigning Moral Judgment

- Early-stage users may be labeled as “experimenters” or “at-risk youth,” implying irresponsibility or poor choices.

- Effect: This can blame the individual for their situation rather than acknowledging environmental, social, or psychological factors.

3. Influencing Clinical Expectations

- Clinicians might assume a patient in a “relapse-prone” stage is less motivated or unreliable, affecting how treatment is delivered.

- Effect: The patient may receive less attention, fewer resources, or less encouragement, reinforcing a negative self-image.

4. Impact on Insurance and Social Systems

- Documentation of “stage” in medical records could label someone as “high-risk” for substance misuse.

- Effect: This might influence insurance coverage, employment opportunities, or legal judgments, leading to systemic stigma.

5. Peer and Community Perception

- If peers or community members learn someone’s “stage,” they may socially isolate or discriminate against them.

- Example: A person in the “escalation” stage of opioid use could be treated with suspicion or excluded from social programs.

6. Self-Stigmatization

- Patients themselves may internalize the stage label:

- Thinking, “I’m in a late stage, so recovery is hopeless,” or

- “I’m just experimenting, so I shouldn’t take treatment seriously.”

- Effect: This can reduce motivation for treatment and reinforce substance use behaviors.

In short, the staging labels can act like a double-edged sword—helpful for clinical planning but potentially harmful if interpreted as fixed judgments about character, potential, or worth.

Conclusion

The SUD staging paradigm offers a structured, stage-specific approach that improves how substance use is understood and addressed. Aligning self-management, family support, and community resources with the individual’s stage ensures interventions are timely, relevant, and effective. This tailored strategy not only enhances prevention and treatment outcomes but also strengthens long-term recovery through coordinated support across personal, familial, and community levels.

Video: The STAGES of Addiction You Need to Know