New treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD) are adapting to fentanyl’s rise, emphasizing low-dose buprenorphine, wider methadone access, and digital or community care. These improve survival and retention but pose risks like withdrawal, sedation, misuse, and ethical dilemmas over autonomy, safety, resources, and balancing harm reduction with abstinence, highlighting a shift toward individualized, evidence-based care.

Evolving Buprenorphine Strategies for Treating Opioid Use Disorder in the Fentanyl Era

Fentanyl has changed the game for treating opioid use disorder (OUD). Unlike heroin or prescription painkillers, fentanyl is far more potent, lingers in the body longer, and creates harder-to-manage withdrawal symptoms. That means older treatment approaches don’t always work well, and doctors are adjusting how they start medications like buprenorphine (Suboxone) to meet today’s challenges.

Why Fentanyl Is Different

- Stronger and stickier: Fentanyl is highly potent and stores itself in body fat, making withdrawal last longer.

- Shorter-acting: People often need to use it more frequently, raising overdose risks.

Because of this, treatment initiation can be more complicated—and sometimes riskier—than with past opioids.

New Approaches to Starting Treatment

1. Emergency Department (ED) Starts

Research shows buprenorphine can be safely started in the ER—even for people using fentanyl—with less than 1% risk of precipitated withdrawal. This makes the ED one of the best places to begin recovery quickly.

2. Traditional vs. Emerging Methods

Traditional Approach

- Wait until moderate withdrawal (6–12 hours for heroin, more protracted for fentanyl).

- Still carries a risk of triggering withdrawal.

Low-Dose Induction (Bernese Method)

- Start with tiny doses while the person continues fentanyl, then increase slowly.

- Designed to prevent withdrawal, but real-world studies show low success and retention rates.

High-Dose Initiation

- Some hospitals start with higher doses (up to 32 mg on day one).

- Provides fast relief but is considered “off-label” in the U.S.

3. Adjusted Protocols for Fentanyl

New guidelines recommend:

- Waiting longer before starting (24+ hours of abstinence).

- Using helper medications like clonidine or anti-nausea drugs.

- Beginning at higher doses (8–16 mg, sometimes up to 32 mg).

4. Extended-Release Buprenorphine (BUP-XR)

This monthly injection helps reduce daily pill or film use and supports long-term retention. Early studies show it’s just as safe as traditional treatments, but access and cost remain challenges.

Quick Comparison

| Strategy | Where It Happens | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED Initiation | ER | Safe, effective, quick relief | Requires ER access |

| Low-Dose (Bernese) | Outpatient/home | Gentle, avoids withdrawal | Low success, poor retention |

| High-Dose Start | ER/clinic | Rapid relief | Off-label, limited availability |

| Adjusted Protocols | Primary care | Tailored to fentanyl | Needs close supervision |

| Extended-Release (BUP-XR) | Clinic/inpatient | Monthly dose, better retention | Expensive, limited access |

In summary, Fentanyl requires flexible, patient-centered treatment. While the emergency department remains a safe entry point, doctors are exploring higher doses, extended-release injections, and supportive medications to improve outcomes. Low-dose starts sound promising, but haven’t shown strong results yet. The bottom line: recovery is possible, but strategies must adapt to the realities of today’s drug supply.

The Side Effects and Challenges of New OUD Medication Start in the Fentanyl Era

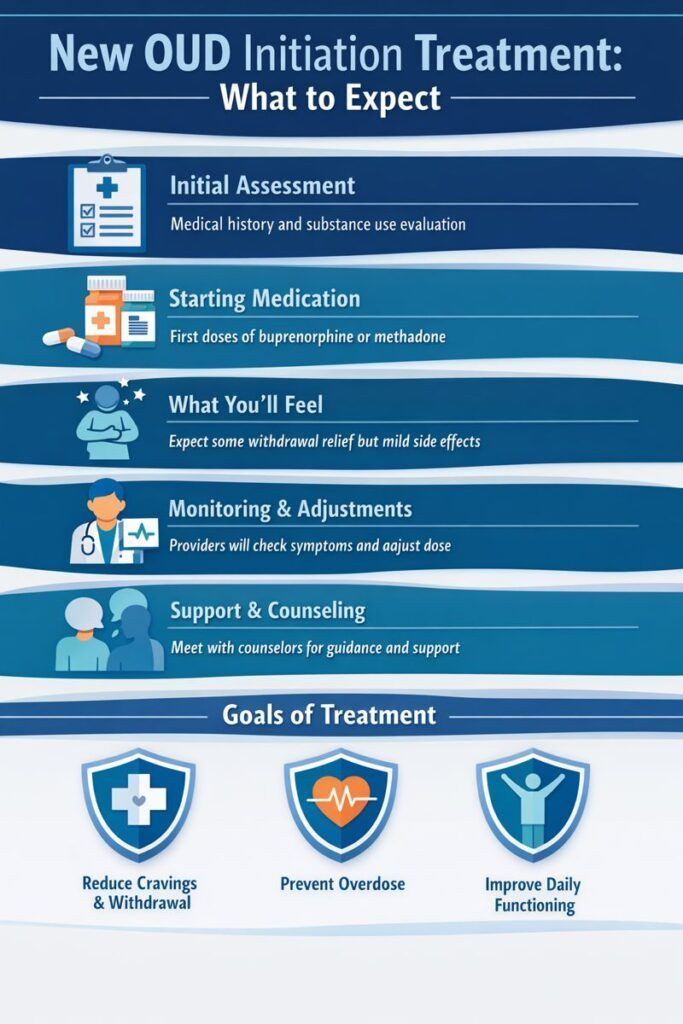

As fentanyl and other high-potency opioids reshape today’s overdose crisis, doctors are updating how they start people on medications for opioid use disorder (OUD). These new approaches can improve safety and access, but they also bring unique side effects and challenges. Here’s what patients and families should know:

1. Emergency Room (ER) Starts

✅ Safe overall, but not perfect

- Rarely (<1%) can still trigger precipitated withdrawal.

- Some patients feel rushed into treatment without fully exploring options.

2. Low-Dose Starts (Microdosing)

- Possible side effects: nausea, headache, sleep problems, sweating.

- Higher risk of treatment dropout before reaching a stable dose.

- Because fentanyl use continues during overlap, overdose risk can remain.

3. High-Dose Starts

- Side effects may include sedation, dizziness, constipation, and headache.

- Doses may feel too intense or overwhelming for newcomers.

- Access is limited—many clinics aren’t yet using this approach.

4. Modified Protocols for Fentanyl

- Require longer waiting times before the first dose, which is tough in withdrawal.

- Extra helper meds (like clonidine or anti-nausea drugs) may cause low blood pressure, dry mouth, or drowsiness.

5. Extended-Release Buprenorphine (BUP-XR Injections)

- It can cause injection site pain, redness, or swelling.

- Harder to adjust the dosage quickly if problems arise.

- Some patients feel less control being “locked in” to a monthly shot.

Big Picture Side Effects

- Physical: Nausea, sweating, constipation, fatigue, sleep changes.

- Psychological: Anxiety or frustration if withdrawal isn’t well managed.

- Practical: Complicated steps (like microdosing or waiting periods) can make treatment harder to stick with.

In summary, while each strategy has trade-offs, experts stress that the benefits of starting treatment far outweigh the risks. These newer approaches are designed to make medication initiation safer, more effective, and more flexible in the fentanyl era—helping more people begin recovery.

Progress and Challenges in Treating Opioid Use Disorder in the Fentanyl Era

Recent data show that treatment strategies for opioid use disorder (OUD) are evolving in response to fentanyl, leading to real improvements in survival rates and overdose prevention. While progress is encouraging, significant gaps remain.

📉 Decline in Overdose Deaths

After peaking in mid-2023, U.S. overdose deaths from synthetic opioids like fentanyl began to fall. By 2024, opioid-related fatalities dropped to about 55,000—a 30% decrease from the year before. Experts credit this to greater access to treatment medications, wider naloxone distribution, and more substantial efforts to disrupt fentanyl supply.

💊 Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) Remains Key

Methadone and buprenorphine continue to be the most effective treatments for OUD—even for people using fentanyl. A 2024 study found that methadone worked just as well as buprenorphine, with nearly all patients who stayed in treatment achieving remission.

Still, treatment duration has been shrinking. A recent study found people who started MAT between 2020–2022 didn’t stay in treatment as long as those who began in earlier years, possibly due to shifting policies and care models.

🧠 Innovative Programs and Digital Support

New approaches are also helping reduce overdose deaths:

- Hotspotting programs in New York use predictive data to identify high-risk individuals, cutting overdose deaths by over 70%.

- Digital tools like smartphone apps that combine therapy and medication management have shown a 35% reduction in opioid use and better treatment retention.

⚠️ Ongoing Challenges

Despite progress, barriers remain:

- In 2022, only 1 in 4 adults with OUD received medication treatment, leaving a significant treatment gap.

- Fentanyl’s extreme potency and widespread polysubstance use make treatment more complicated.

- Some newer strategies, like low-dose buprenorphine starts, show promise but haven’t proven very effective in real-world fentanyl settings, with retention rates as low as 21% after 28 days.

✅ Summary

- Overdose deaths involving fentanyl are finally declining.

- Methadone and buprenorphine remain highly effective, even for fentanyl users.

- Innovative community programs and digital tools are boosting outcomes.

- Significant challenges remain, especially in closing the treatment gap and addressing fentanyl’s unique risks.

👉 The path forward requires expanding access to proven medications, supporting innovative programs, and adapting treatments to fentanyl’s realities. These efforts can further reduce overdose deaths and give more people the chance to recover.

Barriers to Effective Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in the Fentanyl Era

The rise of fentanyl has pushed treatment systems to adapt, but several clinical, regulatory, and societal challenges continue to slow progress. These obstacles highlight the complexity of addressing opioid use disorder (OUD) in today’s drug landscape.

1. Clinical Challenges with Fentanyl-Specific Treatment

Fentanyl’s extreme potency and rapid onset create higher tolerance and stronger cravings, making standard buprenorphine doses (8–16 mg) often insufficient. This raises risks of relapse and overdose.

A 2024 UCSF study on low-dose buprenorphine initiation in fentanyl users found that only 21% of participants remained in treatment after 28 days, showing the urgent need for more effective treatment strategies.

2. Regulatory and Access Barriers

Even with regulatory shifts—like expanded take-home methadone—many people still struggle to access medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). Barriers include:

- Stigma from healthcare providers

- Limited clinical training in addiction medicine

- A shortage of specialists in many communities

In some areas, restrictive policies also slow the integration of MOUD into treatment, limiting their effectiveness.

3. Stigma and Policy Resistance

Stigma remains a powerful barrier. Many patients hesitate to seek treatment, while some providers are reluctant to adopt newer protocols.

At the policy level, funding cuts and political shifts threaten harm reduction programs, risking the loss of hard-won progress in overdose prevention and treatment access.

4. Challenges in Overdose Reversal

Naloxone remains a life-saving tool, but fentanyl’s strength often requires multiple doses to reverse an overdose. Concerns about naloxone access and training—especially in rural or underserved areas—add to the challenge.

In summary, recent treatment innovations show promise, but the fentanyl crisis demands more than minor adjustments. Combating this epidemic will require:

- Improved treatment protocols

- Greater access to MOUD

- Efforts to reduce stigma

- Consistent policy and funding support

A coordinated, research-driven approach is essential to keep pace with the evolving opioid crisis and save more lives.

Ethical Dilemmas in Fentanyl and Opioid Use Disorder Treatment: Balancing Care, Safety, and Justice

The rise of fentanyl has reshaped how opioid use disorder (OUD) is treated, pushing healthcare providers to adopt new medications, flexible dosing strategies, and digital tools. But with these changes come complex ethical dilemmas. Clinicians and policymakers must constantly weigh patient care, public health, and social equity.

1. Access vs. Resource Allocation

Expanding methadone or buprenorphine access can save lives, but resources are limited. Should priority go to high-risk fentanyl users, even if it reduces access for others? Equity is essential, yet prioritization risks leaving some groups behind.

2. Low-Dose Buprenorphine Initiation

Low-dose starts help reduce painful withdrawal for fentanyl users, but retention rates are often lower. This creates a trade-off: prevent short-term harm or focus on long-term recovery. Informed consent is key, so patients can choose what works best for them.

3. Take-Home Methadone and Safety

Giving patients take-home doses boosts convenience and autonomy, but increases risks of diversion or accidental overdose. Providers must balance helping the patient with protecting the community.

4. Harm Reduction vs. Abstinence

Should the goal be complete abstinence—or reducing overdose deaths and improving quality of life, even if some drug use continues? Harm reduction saves lives, but some critics argue it “enables” use.

5. Mandatory Treatment Policies

Some propose mandating treatment for people with repeated overdoses. While this may save lives, it undermines personal autonomy and can erode trust in healthcare.

6. Data Privacy in Digital Tools

Apps and predictive analytics can identify overdose risks, but they also raise concerns about privacy, consent, and stigma if sensitive data is misused.

7. Stigma and Social Justice

People with fentanyl-related OUD face intense stigma, which affects treatment access and funding. Ethical care requires fighting bias and ensuring fair treatment for marginalized populations.

✅ Summary

The ethical dilemmas in fentanyl treatment often revolve around:

- Autonomy – respecting patient choice

- Beneficence – maximizing health benefits

- Nonmaleficence – minimizing harm

- Justice – fair use of limited resources

As fentanyl reshapes the overdose crisis, clinicians, policymakers, and communities must navigate these dilemmas carefully—finding ways to save lives while protecting individual rights and social equity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some common questions:

Question: What are examples of Access vs. Resource Allocation in the new OUD initiation treatment?

Answer: In the context of new OUD (Opioid Use Disorder) initiation treatments, Access vs. Resource Allocation means deciding how limited clinical resources—staff time, medication supply, and treatment slots—are distributed among patients, especially with fentanyl changing treatment needs. Here are concrete examples:

🔹 Examples of Access vs. Resource Allocation

- Prioritizing Fentanyl Users for Buprenorphine Microdosing

- Clinics may offer low-dose/microdosing protocols for fentanyl users, which require more staff oversight, longer appointments, and careful follow-up.

- This may mean patients using heroin, oxycodone, or prescription opioids wait longer for standard buprenorphine starts.

- Methadone Take-Home Flexibility

- Some programs allow fentanyl users faster access to take-home methadone (to reduce overdose risk), but this can limit clinic capacity for new intakes since staff are tied up monitoring compliance.

- Medication Supply Allocation

- In rural or underfunded clinics, the supply of buprenorphine or methadone doses may be limited. Programs may prioritize patients at the highest overdose risk (fentanyl users), leaving others with delayed or reduced access.

- Digital or Telehealth Services

- Expanding telehealth initiation for fentanyl users helps increase survival but requires technology investments, training, and monitoring systems. These resources may not be equally available to patients with other OUDs, widening disparities.

- Specialized Withdrawal Management Beds

- Fentanyl users may need longer detox stays before initiating buprenorphine safely. Hospitals might hold beds for these patients, limiting availability for those withdrawing from alcohol, benzodiazepines, or prescription opioids.

👉 In short, clinics often must decide whether to allocate extra resources to fentanyl patients (to reduce overdoses) or distribute care equally across all OUD patients—even if that could mean higher mortality for those at the most significant risk.

Question: Provide a real-world case study scenario (like a community clinic) example.

Answer: Case Study: Balancing Access and Resources in a Community OUD Clinic.

Setting:

A mid-sized community health clinic in Ohio serves about 500 patients with opioid use disorder. The clinic has recently adapted its protocols to address the rise of fentanyl.

The Challenge:

- The clinic only has two addiction specialists and a limited nursing staff.

- They receive a fixed supply of buprenorphine from a regional distributor each month.

- Many new patients are fentanyl users, who often require low-dose (microdosing) buprenorphine starts that take longer to monitor.

Access vs. Resource Allocation in Action:

- Access Issue: A new patient using fentanyl comes in for help. Clinicians know that if he’s started on standard buprenorphine (8–16 mg), there’s a high risk of precipitated withdrawal. He needs a slow, closely monitored microdosing schedule.

- Resource Allocation Dilemma: Each microdosing patient requires daily check-ins, extra nursing time, and more medication adjustments. If the clinic prioritizes him, they must delay treatment for two patients with prescription opioid dependence who could have been stabilized quickly with a standard buprenorphine induction.

- Decision: The clinic decides to prioritize the fentanyl patient, given the higher overdose risk. To offset resource strain, they shift the prescription opioid patients to telehealth appointments for counseling and schedule their induction later.

Outcome:

- The fentanyl patient is stabilized over 10 days, reducing his immediate overdose risk.

- The other two patients experience frustration over delayed access, but eventually initiate treatment successfully.

- Staff note increased burnout due to the intensity of microdosing protocols, sparking discussions about the need for more funding, staffing, and policy support.

👉 This kind of case study helps readers see that the “access vs. resource allocation” trade-off isn’t just abstract—it plays out daily in real clinics, where decisions about who gets care first and how scarce resources are used are made.

Question: Provide a contrasting case study (like a rural clinic with limited naloxone supply facing tough choices).

Answer: Case Study 2: Rural Clinic Struggles with Naloxone Supply

Setting:

A small rural health clinic in West Virginia serves a wide geographic area but only has one part-time addiction provider. The clinic has limited funding and relies on state grants to supply naloxone.

The Challenge:

- The clinic receives only 100 naloxone kits per month, far below community need.

- Overdose calls have increased, especially involving fentanyl and fentanyl-laced stimulants.

- Local EMS crews often arrive too late due to long travel distances, making community-distributed naloxone crucial.

Access vs. Resource Allocation in Action:

- Access Issue: Families, recovery groups, and schools all request naloxone kits, but there aren’t enough to meet demand.

- Resource Allocation Dilemma: The clinic must decide whether to:

- Prioritize patients currently in OUD treatment (to prevent relapse or overdoses), or

- Distribute naloxone more broadly to high-risk community members (people not in treatment, such as those actively using).

- Decision: The clinic chooses to prioritize community distribution, reasoning that those outside treatment are at the highest overdose risk. Patients in treatment are offered overdose prevention education and encouraged to share naloxone kits with peers.

Outcome:

The provider uses these data to lobby state policymakers for increased funding for naloxone.

Several overdose reversals are reported in the community thanks to the broader naloxone access.

Patients in treatment express frustration at not receiving personal kits, raising concerns about equity.

Conclusion

The new treatment approaches for OUD in the era of fentanyl represent a critical advancement in addressing a complex and deadly crisis. By tailoring interventions such as low-dose buprenorphine, expanded methadone access, and digital or community-based support, these strategies improve survival and treatment retention despite side effects like withdrawal and sedation. However, their implementation also raises ethical challenges, including ensuring patient autonomy, promoting equitable resource allocation, and balancing harm reduction with societal expectations of abstinence. Overall, these developments highlight the need for continued innovation, careful ethical consideration, and a patient-centered approach to combat fentanyl-related OUD effectively.

Videos:

The FASTEST Way to Beat OUD with Low-Dose Treatment

Top Addiction Expert Reveals MICRO INDUCTION Method for Faster Opioid Recovery