Methadone is one of the most effective and evidence-based treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD), significantly reducing cravings, withdrawal symptoms, overdose risk, and illicit opioid use. Despite its proven effectiveness, access to methadone remains highly regulated and unevenly distributed. Strict dispensing requirements, limited clinic locations, daily attendance mandates, transportation challenges, stigma, and socioeconomic barriers all restrict who can realistically engage in treatment. These accessibility barriers disproportionately affect rural communities, marginalized populations, and individuals facing housing or employment instability, limiting the full public health impact of this life-saving medication.

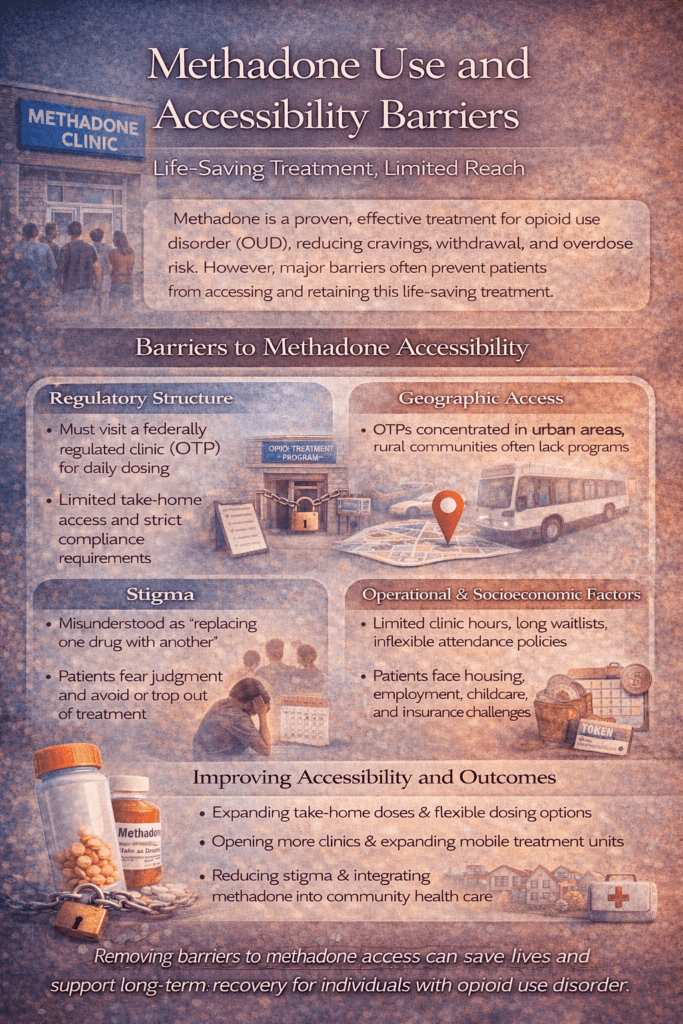

Methadone Use and Accessibility Barriers: Life-Saving Treatment, Limited Reach

Methadone is one of the most effective, evidence-based treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD). When used appropriately, it reduces opioid cravings, prevents withdrawal, lowers overdose risk, and improves long-term retention in treatment. Despite decades of evidence supporting its effectiveness, access to methadone remains highly restricted, creating significant barriers for individuals who could benefit most from this life-saving medication.

One of the primary accessibility barriers is the regulatory structure. In many countries, including the United States, methadone for OUD can only be dispensed through federally regulated opioid treatment programs (OTPs). Unlike other medications, it cannot be prescribed for take-home use through standard outpatient clinics at treatment initiation. This requirement forces patients to attend clinics daily, often for months or years, regardless of employment, caregiving responsibilities, or health limitations.

Geographic access is another major challenge. OTPs are disproportionately located in urban areas, leaving rural and underserved communities with limited or no access. For many patients, daily travel involves long distances, unreliable transportation, or a significant financial burden. These obstacles can discourage treatment initiation and contribute to early dropout, even when motivation for recovery is high.

Stigma also plays a powerful role in limiting access. Methadone treatment has long been misunderstood and unfairly characterized as “replacing one drug with another.” This stigma affects public policy, healthcare systems, employers, families, and patients themselves. Fear of judgment or discrimination can prevent individuals from seeking methadone treatment or remaining engaged once enrolled.

Operational barriers within treatment programs further complicate access. Limited clinic hours, long waitlists, inflexible attendance policies, and strict compliance requirements can unintentionally exclude individuals with unstable housing, co-occurring mental health conditions, or irregular work schedules. For many, the structure designed to ensure safety becomes a barrier to care.

Socioeconomic factors also influence methadone accessibility. Individuals without stable housing, insurance, childcare, or paid time off often face impossible choices between attending treatment and meeting basic survival needs. These pressures disproportionately affect marginalized populations already at higher risk for overdose and untreated OUD.

Despite these challenges, policy changes during public health emergencies have demonstrated that flexibility improves outcomes. Expanded take-home doses, telehealth integration, and reduced administrative burden have shown that methadone can be delivered safely with fewer restrictions. These changes have improved retention, reduced patient burden, and enhanced quality of life without increasing harm.

Methadone is not the problem—access is. Addressing accessibility barriers requires reexamining outdated regulations, expanding treatment locations, reducing stigma, and prioritizing patient-centered care. When methadone is accessible, flexible, and treated as essential medical care, it fulfills its potential to save lives and support long-term recovery.

Self-Management Strategies for Methadone Use Amid Accessibility Barriers

Methadone is a highly effective treatment for opioid use disorder, yet many individuals face significant accessibility barriers that make consistent engagement difficult. Daily clinic visits, transportation challenges, work and caregiving responsibilities, stigma, and rigid program requirements can all interfere with treatment continuity. In this context, self-management strategies become essential tools that help individuals remain engaged, stable, and supported despite systemic limitations.

One foundational self-management strategy is routine and planning. Methadone is most effective when dosing is consistent, and accessibility barriers often disrupt schedules. Creating a structured daily routine around clinic visits—such as setting alarms, planning transportation in advance, and building buffer time—reduces missed doses and stress. Written schedules or phone reminders can be especially helpful during early treatment.

Transportation planning is another critical skill. For individuals traveling long distances or relying on public transit, identifying backup options in advance can prevent missed doses. This may include coordinating rides with trusted supports, using transportation assistance programs, or adjusting work hours when possible. Proactive planning increases reliability and reduces the anxiety associated with daily attendance.

Communication and self-advocacy within treatment programs also improve outcomes. Patients who openly discuss barriers—such as work conflicts, side effects, childcare needs, or mental health symptoms—are more likely to receive accommodations or support. Advocating for dose adjustments, counseling flexibility, or take-home eligibility when appropriate helps align treatment with real-life needs.

Managing stigma and emotional stress is another essential self-management strategy. Internalized stigma, frustration, and fatigue can undermine motivation to stay in treatment. Practices such as journaling, peer support, mindfulness, and counseling help individuals process these experiences and maintain a recovery-focused mindset. Reframing methadone as legitimate medical care—not a personal failure—supports self-worth and persistence.

Health maintenance further strengthens self-management. Adequate sleep, hydration, nutrition, and stress regulation improve methadone tolerance and overall well-being. Attending to physical and mental health reduces side effects and supports long-term engagement, especially when treatment demands are high.

Finally, goal setting and progress tracking help sustain motivation. Recognizing improvements such as reduced cravings, improved stability, employment, or healthier relationships reinforces the value of staying in treatment despite barriers. Small, measurable goals shift focus from daily inconvenience to long-term gains.

Self-management strategies do not eliminate accessibility barriers to methadone treatment, but they help individuals navigate them more effectively. When patients are supported in building routines, advocating for their needs, managing stress, and maintaining perspective, methadone treatment becomes more sustainable. These skills empower individuals to remain engaged in life-saving care while broader systems work toward more equitable access.

Family Support Strategies for Methadone Use Amid Accessibility Barriers

Methadone is a proven, life-saving treatment for opioid use disorder, yet many individuals face significant accessibility barriers that make consistent engagement difficult. Daily clinic visits, transportation demands, stigma, rigid program requirements, and competing responsibilities can strain even the most motivated patients. Family support plays a critical role in helping individuals navigate these barriers and remain engaged in treatment long enough for recovery to take hold.

One of the most important family strategies is adopting an informed, nonjudgmental stance toward methadone treatment. Misunderstanding methadone as “replacing one drug with another” can undermine support and increase shame. Families who learn how methadone stabilizes brain chemistry, reduces overdose risk, and supports long-term recovery are better positioned to encourage continued engagement rather than pressuring premature tapering or discontinuation.

Practical support significantly improves treatment consistency. Families can assist with transportation to clinics, help coordinate schedules, provide childcare during dosing hours, or offer reminders for appointments and paperwork. These seemingly small supports reduce stress and logistical obstacles that often lead to missed doses or dropout, especially during early treatment.

Emotional support is equally essential. Daily clinic attendance and stigma can be exhausting and demoralizing. Families who offer encouragement, acknowledge effort, and recognize progress—such as improved stability, health, or relationships—help sustain motivation. Validating the challenges of treatment without minimizing its importance fosters resilience and persistence.

Healthy boundaries also strengthen family support. Supporting methadone treatment does not mean ignoring unsafe behaviors or sacrificing personal well-being. Clear, consistent boundaries around safety, communication, and responsibilities help maintain trust and accountability while avoiding control or punishment that can push individuals away from care.

Advocacy is another powerful family strategy. Families can help individuals communicate with treatment programs, navigate insurance issues, and access community resources, such as transportation assistance and counseling. When appropriate and welcomed, family involvement can amplify the patient’s voice and help align treatment with real-world needs.

Finally, families must care for themselves. Supporting someone facing systemic barriers can lead to burnout, frustration, or fear. Family counseling, education programs, and peer support groups help loved ones process their own experiences and remain effective, compassionate allies in recovery.

When families combine education, practical assistance, emotional encouragement, boundaries, and advocacy, they become a stabilizing force in methadone treatment. In the face of accessibility barriers, family support can make the difference between disengagement and sustained, life-saving care—turning treatment from an individual burden into a shared commitment to recovery.

Community Resource Strategies for Methadone Use Amid Accessibility Barriers

Methadone is a gold-standard treatment for opioid use disorder, yet access remains constrained by regulatory, geographic, logistical, and social barriers. Community resources play a crucial role in closing these gaps by supporting continuity of care, reducing daily burdens, and helping individuals remain engaged in life-saving treatment despite systemic limitations.

Peer recovery support services are among the most impactful community strategies. Peer specialists with lived experience of methadone treatment offer practical guidance, emotional validation, and navigation support that traditional systems may lack. Regular peer contact reduces isolation, mitigates stigma, and encourages persistence during periods of fatigue or frustration associated with daily clinic attendance.

Recovery community centers also strengthen methadone access by providing low-barrier, nonjudgmental spaces for connection and support. These centers often offer support groups, wellness activities, employment readiness, and social connection without requiring abstinence or rigid participation rules. By reinforcing a sense of belonging and routine, they help individuals stay recovery-oriented even when clinic demands feel overwhelming.

Transportation assistance programs are another critical resource. Community organizations that provide bus passes, ride vouchers, shuttle services, or volunteer drivers directly address one of the most common reasons for missed doses and dropouts. Reliable transportation can mean the difference between consistent treatment engagement and unintentional disengagement.

Harm reduction services further enhance methadone accessibility. Syringe service programs, naloxone distribution, overdose education, and infectious disease screening often serve as trusted entry points into care. These programs keep individuals connected to supportive systems and can facilitate referral and re-engagement with methadone treatment when readiness fluctuates.

Community health clinics and integrated care models also reduce barriers to access. Clinics that coordinate primary care, mental health services, and social support alongside methadone treatment address co-occurring conditions that interfere with retention. Integrated care reduces fragmentation and helps individuals manage health needs without navigating multiple disconnected systems.

Housing, employment, and legal aid services also play a vital supporting role. Stable housing, income support, and legal advocacy reduce the survival stressors that compete with daily clinic attendance. Addressing social determinants of health makes methadone treatment more feasible and sustainable.

Finally, community education and stigma-reduction initiatives improve the broader treatment environment. Public understanding of methadone as legitimate, evidence-based medical care reduces discrimination and supports policies that expand access and flexibility.

Community resource strategies do not replace methadone treatment—they make it possible. By reducing logistical burdens, offering connection and advocacy, and addressing social needs, communities help transform methadone from a difficult daily obligation into a sustainable pathway to recovery.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some common questions:

What is methadone, and how does it work?

Methadone is a long-acting opioid medication used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD). It reduces cravings and withdrawal symptoms by stabilizing opioid receptors in the brain, helping individuals function normally without the highs and lows associated with illicit opioid use.

Is methadone effective for opioid use disorder?

Yes. Methadone is one of the most extensively studied treatments for OUD and is proven to reduce overdose risk, improve treatment retention, decrease illicit opioid use, and support long-term recovery when taken as prescribed.

Why is access to methadone so restricted?

In many countries, including the United States, methadone for OUD can only be dispensed through federally regulated opioid treatment programs (OTPs). These regulations were designed for safety, but now limit access by requiring daily clinic visits and restricting prescribing flexibility.

What are the most common accessibility barriers to methadone treatment?

Common barriers include limited clinic locations, especially in rural areas; daily travel requirements; transportation challenges; inflexible clinic hours; long waitlists; insurance or cost issues; and stigma associated with methadone use.

How does stigma affect methadone access?

Stigma leads to misconceptions such as the belief that methadone “replaces one addiction with another.” This can discourage individuals from seeking treatment, influence policy decisions, and affect employment, housing, and social support for people receiving methadone.

Why do daily clinic visits create problems for patients?

Daily visits can interfere with work, childcare, school, medical appointments, and other responsibilities. They also increase transportation costs and time burdens, which can lead to missed doses or early dropout from treatment.

Are take-home methadone doses allowed?

Yes, but access is limited and typically requires meeting strict criteria over time. Eligibility varies by regulation and program policy. Expanded take-home access during public health emergencies has been shown to improve retention and quality of life without increasing harm.

How do accessibility barriers affect treatment retention?

When treatment demands exceed a person’s ability to meet them, individuals may miss doses, disengage from care, or return to illicit opioid use. Poor retention increases the risk of relapse and overdose.

Who is most affected by methadone accessibility barriers?

Barriers disproportionately affect people in rural areas, individuals with unstable housing, those without reliable transportation, people with inflexible jobs, caregivers, and marginalized populations already facing healthcare inequities.

What role do community resources play in improving access?

Community resources, such as peer recovery support, transportation programs, recovery community centers, harm reduction services, and integrated healthcare models, help reduce logistical and emotional barriers and maintain individuals’ engagement in care.

Can methadone be provided more flexibly and safely?

Yes. Evidence from expanded take-home policies, mobile methadone units, and integrated care models shows that methadone can be delivered safely with greater flexibility while maintaining effectiveness and reducing patient burden.

What is the key takeaway about methadone access?

Methadone saves lives, but access barriers limit its impact. Reducing regulatory restrictions, expanding clinic availability, addressing stigma, and integrating methadone into community healthcare are essential steps toward equitable, patient-centered OUD treatment.

Conclusion

Addressing accessibility barriers to methadone treatment is essential for improving retention, reducing overdose deaths, and promoting equitable recovery opportunities. Expanding clinic availability, increasing flexibility in take-home dosing, integrating methadone into broader healthcare settings, reducing stigma, and strengthening community support systems can significantly improve access to care. Methadone itself is not the obstacle—system-level barriers are. When policies and care models prioritize patient-centered, evidence-based access, methadone can fulfill its potential as a cornerstone of effective and compassionate opioid use disorder treatment.

Video: Methadone Could Save Your Life—If You Can Actually Get It #OUDRecovery #AccessMatters