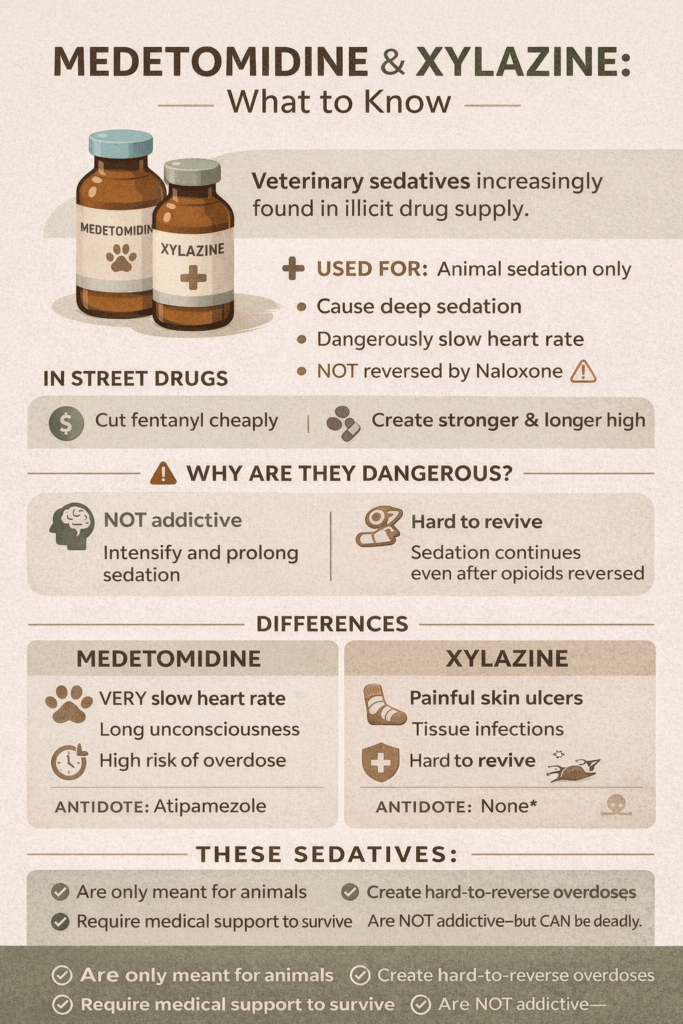

Medetomidine and xylazine are powerful veterinary sedatives that were never intended for human use, yet they are increasingly appearing in the illicit drug supply. Both drugs belong to a class of medications that slow the nervous system, producing deep sedation, reduced breathing, and lowered heart rate. Because they do not activate the brain’s reward system, neither medetomidine nor xylazine is addictive in the traditional sense. However, when mixed with opioids like fentanyl, they intensify and prolong sedation, making overdoses more severe and harder to reverse. Their growing presence in street drugs has created a new challenge for harm reduction workers, healthcare providers, and communities trying to respond to an evolving overdose crisis.

Medetomidine vs. Xylazine: What’s the Difference?

Veterinary sedatives have quietly entered the conversation around the overdose crisis. Two names now appearing in toxicology reports and drug-checking programs are medetomidine and xylazine. Both were developed for animal sedation, not human use. Yet both are increasingly found in the illicit opioid supply, raising urgent questions: What do they do? How are they different? And are they addictive?

Medetomidine and xylazine belong to the same drug class: alpha-2 adrenergic agonists. In veterinary medicine, they safely calm animals, relieve pain, and relax muscles during procedures. They work by reducing norepinephrine in the brain, slowing the heart rate, lowering blood pressure, and decreasing breathing rate. In controlled medical settings, these effects are monitored and reversible. In the human body—especially when mixed with opioids—these effects can become unpredictable and life-threatening.

A common misconception is that these drugs are addictive. Neither medetomidine nor xylazine activates the brain’s dopamine reward system. They do not cause euphoria, cravings, or compulsive drug-seeking behavior. Therefore, they are not addictive in the traditional sense. What they do cause is intense sedation, memory gaps, and prolonged unconsciousness. When combined with fentanyl, this heavy sedation can make the opioid feel stronger or last longer. Users may return to the drug mixture due to opioid dependence, not because of addiction to the sedative itself.

While they share many similarities, their risks differ.

Medetomidine is more strongly associated with:

- Extreme slowing of heart rate

- Prolonged unconsciousness

- Hard-to-reverse sedation

Xylazine is more strongly associated with:

- Severe skin ulcers

- Tissue necrosis

- Infection and wound complications

- Risk of amputation

Both suppress breathing. Both lower blood pressure. And critically, neither is reversed by naloxone. This means that during an opioid overdose, naloxone may restore breathing, but sedation from medetomidine or xylazine can continue — leaving the person unconscious and medically unstable even after opioid reversal.

So why are they appearing in street drugs?

The answer is cost and effect. These veterinary sedatives are inexpensive and easily sourced through veterinary supply channels. When added to fentanyl, they increase the duration of sedation and create the impression of a stronger product. Unfortunately, this also dramatically increases overdose risk, delays recovery, and complicates emergency response.

Legally, both medetomidine and xylazine are approved only for veterinary use. When manufactured, sold, or mixed into drugs intended for human consumption, their distribution becomes illegal. As testing technology improves, public health agencies are now tracking these substances as part of the evolving overdose epidemic.

The presence of medetomidine and xylazine in street drugs reflects a changing drug landscape. Today’s overdose crisis is no longer driven by opioids alone, but by combinations of powerful sedatives that prolong unconsciousness and suppress vital functions.

Neither drug is addictive — but both can be deadly. Understanding the difference is key to effective harm reduction, treatment planning, and saving lives.

Why Medetomidine and Xylazine Overdoses Are Hard to Treat

Medetomidine and xylazine have become dangerous contaminants in the illicit opioid supply, and one of the most alarming realities is that overdoses involving these drugs are far harder to treat than opioid-only overdoses. The difficulty comes from how these substances affect the body and how little our standard emergency tools can reverse their effects.

1. They are not opioids, so naloxone doesn’t work on them

Naloxone is the life-saving medication used to reverse opioid overdoses. It works by knocking opioids off their receptors in the brain and restoring normal breathing.

However, medetomidine and xylazine are not opioids. They act on alpha-2 adrenergic receptors instead. This means:

- Naloxone can reverse the effects of fentanyl or heroin

- But sedation from medetomidine or xylazine continues

- The person may remain unconscious even after multiple naloxone doses

This creates confusion in emergency response because a person may appear “revived” from the opioid but still be in a medical crisis from the sedative.

2. They cause extreme respiratory depression

Both drugs slow breathing independently of opioids.

When combined with fentanyl, breathing can drop to dangerously low levels or stop entirely. Even after opioid reversal, breathing may not return to normal, requiring oxygen support or mechanical ventilation.

3. They severely slow the heart rate and blood pressure

Medetomidine especially causes:

- Profound bradycardia (very slow heart rate)

- Low blood pressure

- Poor circulation

This can lead to cardiac arrest if not medically supported — something naloxone cannot fix.

4. They cause prolonged unconsciousness

Unlike short-acting opioids, these sedatives can last hours.

People may remain unresponsive long after the opioid effect wears off, increasing risks of:

- Aspiration (choking on vomit)

- Brain injury from a lack of oxygen

- Physical trauma from being unconscious

5. There is no widely available human antidote

In veterinary medicine, medetomidine and xylazine can be reversed with atipamezole.

But this reversal drug:

- Is not approved for human use

- Is rarely available in emergency settings

- Has limited research on human overdose care

So emergency teams must rely solely on supportive care: oxygen, airway management, IV fluids, and heart monitoring.

6. Xylazine adds wound complications

Xylazine also reduces blood flow to the skin, leading to:

- Severe ulcers

- Tissue death

- Infection

These injuries complicate recovery long after overdose survival.

Summary

Opioid overdoses are treatable because naloxone directly reverses them.

Medetomidine and xylazine overdoses are harder to treat because they create deep sedation, slow breathing, and heart suppression that naloxone cannot reverse. Treatment requires hospital-level respiratory and cardiac support — resources not always available in community overdose settings.

Community Resource Strategies for Medetomidine and Xylazine Education

Community resources and strategies that can help educate individuals, families, and communities about medetomidine and xylazine — particularly in the context of the evolving drug supply and overdose prevention.

📌 1. National Public Health Agencies

☑️ SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration)

Provides comprehensive national resources for substance use education, treatment referrals, and prevention toolkits. Good entry point for community education and to link into local services.

☑️ CDC — Xylazine Information Page

Centers for Disease Control offers detailed guidance on what xylazine is, its risks, and how community groups can spread awareness about its presence in the drug supply.

📌 2. Harm Reduction Organizations

☑️ National Harm Reduction Coalition

A leading national nonprofit promoting evidence-based harm reduction strategies like overdose prevention, syringe access, training, and community education.

☑️ NEXT Harm Reduction

Nonprofit that distributes naloxone, sterile syringes, and other harm reduction supplies by mail, extending access to communities across the U.S.

📌 3. Local Harm Reduction and Support Programs

Community-level organizations often offer tailored education on drug supply risks, overdose prevention, and safer use practices.

Examples (illustrative community models):

- Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) – provide sterile equipment, drug testing supplies, and education on local drug trends.

- Take-Home Naloxone Programs – train community members and deliver naloxone kits to prevent opioid overdose deaths.

- Local health department harm-reduction branches – offer naloxone training, drug-checking information, and public campaigns (e.g., Kentucky Harm Reduction).

📌 4. Educational & Support Outreach in Healthcare Settings

Healthcare systems, especially in areas hit hard by emerging sedatives, are developing direct outreach and wound care education programs for people affected by xylazine and similar drugs — creating opportunities for community partnerships.

📌 5. Overdose Prevention Coalitions and Response Teams

Local overdose response teams (often called QRTs or DARTs) combine first responders, counselors, and public health workers to educate, respond after overdoses, and connect individuals to services.

📌 6. Drug Checking & Surveillance Partnerships

Drug-checking programs (through public health or community partners) help people test substances for adulterants like fentanyl, xylazine, and other contaminants — offering real-time education about what’s in the local drug supply.

💡 How These Resources Support Education

Across all of these resources, education efforts typically include:

- Overdose awareness training (recognition, naloxone use)

- Harm reduction workshops (safer use, test strips, wound care)

- Drug-checking information on sedatives and adulterants

- Public education campaigns on the changing drug supply

- Referral networks to treatment and recovery services

🎯 Tips for Community Educators

To effectively educate about medetomidine and xylazine:

- Integrate into existing harm reduction training rather than isolated topics

- Partner with local health departments and nonprofits for credibility

- Use plain-language messaging about sedation risk and naloxone limits

- Include multiple audiences — people who use drugs, families, schools, and first responders

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some common questions:

1. What are medetomidine and xylazine?

Medetomidine and xylazine are veterinary sedatives used to calm animals during medical procedures. They slow the nervous system, heart rate, and breathing. They are not approved for human use.

2. Why are they showing up in street drugs?

Drug suppliers add them to fentanyl or heroin to make the effects feel stronger and longer-lasting. They are cheap, easy to obtain through veterinary supply chains, and increase sedation.

3. Are medetomidine and xylazine addictive?

No. They are not addictive in the traditional sense because they do not create euphoria or trigger dopamine in the brain. People become addicted to the opioids they are mixed with — not the sedatives themselves.

4. If they aren’t addictive, why are they dangerous?

They cause deep sedation, slow breathing, and a very low heart rate. When combined with opioids, they dramatically increase overdose risk and prolong unconsciousness.

5. Can naloxone reverse these drugs?

No. Naloxone only reverses opioids.

It can restore breathing from fentanyl or heroin, but medetomidine and xylazine sedation continue, often requiring hospital-level care.

6. Why are overdoses involving these drugs harder to treat?

Because they suppress breathing and heart function independently of opioids, and there is no approved human antidote. Emergency care focuses on oxygen, airway support, and heart monitoring.

7. What is the difference between medetomidine and xylazine?

Medetomidine is more associated with:

- Extremely slow heart rate

- Prolonged unconsciousness

Xylazine is more associated with:

- Severe skin ulcers

- Tissue damage

- Infection risk

Both cause heavy sedation and respiratory depression.

8. Are these drugs legal?

They are legal only for veterinary use.

When sold, mixed, or distributed for human consumption, they become illegal substances.

9. How can people reduce risk?

- Never use alone

- Carry naloxone

- Test drugs when possible

- Seek medical help if someone remains unconscious after naloxone

- Watch for slow or stopped breathing

10. Why is community education important?

Because the drug supply is changing. Understanding that these sedatives are not addictive but life-threatening helps communities respond faster, prevent deaths, and connect people to care.

Conclusion

Although medetomidine and xylazine do not cause cravings or compulsive drug use, their impact on the body makes them extremely dangerous when used outside veterinary medicine. Their strong sedative effects suppress breathing and heart function, and unlike opioids, their effects cannot be reversed with naloxone. This results in longer periods of unconsciousness, a higher risk of fatal overdose, and more complex medical emergencies. As these substances continue to infiltrate the illicit drug supply, education, drug-checking access, and community awareness are essential to reducing harm. Understanding that these drugs are not addictive—but are life-threatening—helps communities better prepare for prevention, response, and recovery in today’s changing drug landscape.

Video: Medetomidine and Xylazine Are Changing the Game #drugsafety #fentanyl